Cultural History

Help Us Discover Our Past

Do you have history at Butano State Park? From pioneer homesteads to logging camps, a lot has happened in the quiet redwood canyons of Butano. If your family was once part of the parks past we would love to hear from you.Contact Mike Merritt

California State Park Interpreter I

mike.merritt@parks.ca.gov

The name Butano probably came from the Spanish name for a drinking cup made from a bull’s horn. The park’s history has been shaped by native people, European explorers and settlers, and, more recently, loggers and preservationists.

Native People

The human and natural histories of Butano State Park are closely linked. Though the indigenous people profoundly altered the natural landscape, they also remained intimate with it and dependent upon it.

When the first Spanish explorers reached California after 1769, what is now Butano State Park lay within the territory of the Quiroste tribe—a large group of Native Americans who had settled the area many thousands of years before. The Quiroste hunted game, harvested plant foods, dined on a great variety of seafoods and sold coastal resources to their inland neighbors using shell beads as money. In autumn, the people burned large tracts of meadowlands to manage the foods they ate—especially hazelnuts and acorns. The fires improved plants that fed the deer, pronghorn and tule elk they hunted. Their once-managed landscape has reverted to wilderness.

In the San Francisco and Monterey Bay regions, the Quiroste numbered among more than fifty tribes whose descendants are today called the Ohlone.

European Settlement

European migration brought new settlers to the region, beginning with the 1769 Portolá expedition. The new crops and grazing animals cultivated by these settlers decimated traditional Quiroste food sources, so most of the Quiroste gave up their land and were taken into the Spanish mission system. Some Quiroste hid in the mountains. After the missions were secularized in 1834, the land passed into private hands.

California Settlement

Following the Gold Rush, large numbers of Americans began arriving in California. In 1850, California became a state, and thousands of acres of rancho property began to be turned over to American citizens. Many of the large ranchos were purchased by wealthy European Americans. In 1851, Isaac Graham of Santa Cruz acquired the Rancho Punta de Año Nuevo from the Castro heirs, encompassing all of what would become Butano SP. Graham was a longtime California resident, and one of its most infamous personages. Although he did not live on the rancho, he leased much of the land out for cattle ranching. Because of financial troubles, Graham was unable to hold onto the property, and it was sold at public auction in 1862 to John H. Baird, for $20,000. Baird quickly sold the property to Loren Coburn for $30,000. Coburn purchased both the Rancho Butano and Rancho Punta de Año with his brother-in-law Jeremiah Clark. After buying out Clark, Coburn leased much of the land to a northern California family dairy enterprise by the name of Steele.

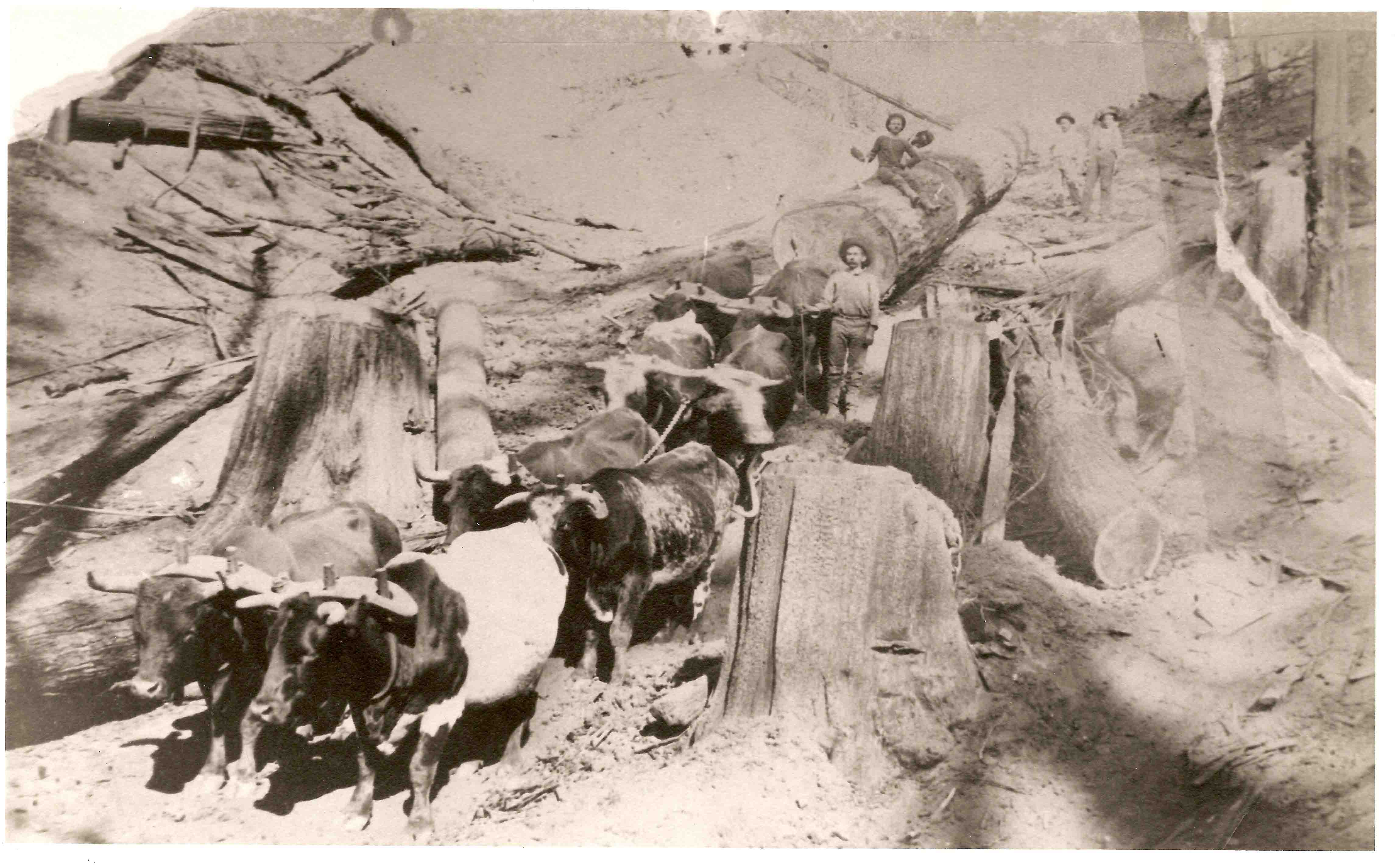

Lumbering

With abundant old growth forests, lumbering became a prominent economic activity in the Butano region. As settlement south of San Francisco grew, the redwood trees prevalent in the Santa Cruz Mountains were exploited for their commercial use. While the eastern slopes up to the summit were harvested beginning in the 1850s, the coastside areas were further from shipping points, markets, and transportation facilities, making logging operations difficult. By the 1870s, the accessible timber on the eastern slope had been largely harvested. Logging then focused on the coastside watersheds of the Purisima, Tunitas, San Gregorio, Pescadero, and Gazos creeks. Most local creeks dried up in the summer, requiring steampowered mills for effective logging operations. Small shingle mills were often set up in small, remote canyons where oxen teams could not reach. Transporting the lumber to market proved extremely difficult and expensive. With no deep water port on the nearby coast, shipping the lumber from the few small wharfs (Waddell’s, Gordon’s Chute at Tunitas, Pigeon Point) was generally not cost effective. Prices of lumber also varied widely, based upon changing demand as the result of fires or other disasters. These price fluctuations frequently put small operations out of business. Nevertheless, several mills were established on the coast side of the mountains beginning in 1867, and some businesses thrived for a time.

The focus of most early lumbering in the area appears to have been along Gazos Creek. The Birch and Steen shingle mill was located approximately 0.5 miles west of the confluence of Bear Creek and Gazos Creek, and about five miles from the ocean. It was eventually sold to Horace Templeton who moved the mill upstream, began milling lumber, and organized the Pacific Lumber and Mill Company. Lumber was floated down a flume to the intersection of Cloverdale Road and Gazos Creek Road where it was hauled to Pigeon Point for shipping. Despite a promising beginning, the mill closed following the death of Templeton in 1873. The nationwide Panic of 1873 put several other mills in the Santa Cruz Mountains out of business. It would be several years before business would begin to pick up again. In 1882, James McKinley (brother of the future president) reactivated the Pacific Lumber mill, and soon was supplying the increasingly powerful and expanding Southern Pacific Railroad. The mill was renamed the “McKinley Mill”. Business continued to ebb and flow based upon the larger national, regional, and local economies.

The focus of most early lumbering in the area appears to have been along Gazos Creek. The Birch and Steen shingle mill was located approximately 0.5 miles west of the confluence of Bear Creek and Gazos Creek, and about five miles from the ocean. It was eventually sold to Horace Templeton who moved the mill upstream, began milling lumber, and organized the Pacific Lumber and Mill Company. Lumber was floated down a flume to the intersection of Cloverdale Road and Gazos Creek Road where it was hauled to Pigeon Point for shipping. Despite a promising beginning, the mill closed following the death of Templeton in 1873. The nationwide Panic of 1873 put several other mills in the Santa Cruz Mountains out of business. It would be several years before business would begin to pick up again. In 1882, James McKinley (brother of the future president) reactivated the Pacific Lumber mill, and soon was supplying the increasingly powerful and expanding Southern Pacific Railroad. The mill was renamed the “McKinley Mill”. Business continued to ebb and flow based upon the larger national, regional, and local economies.

Pescadero

By the early 1860s, the small town of Pescadero had emerged along this portion of the San Mateo Coast, and was soon served by several stage lines. Aside from Half Moon Bay, Pescadero was the only other town of any size during this period. By 1868 Pescadero had become the fourth largest town in the county (having just been annexed by San Mateo County that year). The town thrived as a result of it being a transportation hub for adjacent farms and lumber mills. Stages ran from Redwood City over the mountains via Searsville and La Honda to Pescadero. During periods of bad weather, mail and passenger stages were routed through Boulder Creek, passing through what is now Butano SP. The route followed those used by California Indians, along the ridgelines along Little Butano and Gazos. These routes were used until the 1880s. By the turn-of-the-century, the long anticipated Ocean Shore Railroad that was to connect San Francisco with the San Mateo coastal area (en route to Santa Cruz) was finally being built. The anticipated contracts to supply the railroad with ties led to more lumbering activity in the mountains. By this time, the advent of the steam donkey engine and new circular saw in the 1880s led to more efficient logging operations and a greater depletion of old growth redwoods. Following the 1906 earthquake, which devastated San Francisco, demand for lumber rose again. Many fled the city for the bayside of the peninsula, which also led to increased demand for lumber. Several mills were built on Gazos Creek, as well as other locations (such as on Butano and Little Butano Creeks).

Homesteads

Though most of the Santa Cruz Mountains were too rugged to be suitable for homesteading, the canyon of Little Butano Creek was one notable exception. There are several areas of flat open spaces that allowed for limited farming and ranching. The most pronounced of these consist of Little Butano Flats (at the entrance to the current park), Jackson Flats immediately below the north ridge, and Goat Hill on the south ridge. One of the first to arrive was William Jackson and his wife Isabella, who filed on three separate 160 acre parcels of land in 1861. Jackson built a small house in the heart of his property, on the north side of the canyon. The area in which they settled became known as Jackson Flats. Jackson eventually acquired a total of 400 acres, and had four children, Mary, William, Fannie, and Thomas. E.P. Mullen homesteaded on the south side of Little Butano canyon in the early 1860s. Mullen established a goat ranch on the property, giving the name to Goat Hill. Mullen’s daughter continued to live on the ranch with her husband, William M. Taylor. The Taylors remained until the late 1800s. In 1873, Taylor built a shingle mill on the south bank of Little Butano Creek. Partnering with William Jackson, the two operated the mill for almost 10 years. By the 1880s, Sheldon “Pudy” Pharis had purchased property in the upper Little Butano basin. Known as the “shingle king,” Pharis built one of the first shingle mills in the Santa Cruz Mountains in 1863, and apparently operated as many as seven mills. Pharis purchased the Taylor mill, along with many others in the area. In 1885, however, Pharis committed suicide, and the mill ceased operation.

Though most of the Santa Cruz Mountains were too rugged to be suitable for homesteading, the canyon of Little Butano Creek was one notable exception. There are several areas of flat open spaces that allowed for limited farming and ranching. The most pronounced of these consist of Little Butano Flats (at the entrance to the current park), Jackson Flats immediately below the north ridge, and Goat Hill on the south ridge. One of the first to arrive was William Jackson and his wife Isabella, who filed on three separate 160 acre parcels of land in 1861. Jackson built a small house in the heart of his property, on the north side of the canyon. The area in which they settled became known as Jackson Flats. Jackson eventually acquired a total of 400 acres, and had four children, Mary, William, Fannie, and Thomas. E.P. Mullen homesteaded on the south side of Little Butano canyon in the early 1860s. Mullen established a goat ranch on the property, giving the name to Goat Hill. Mullen’s daughter continued to live on the ranch with her husband, William M. Taylor. The Taylors remained until the late 1800s. In 1873, Taylor built a shingle mill on the south bank of Little Butano Creek. Partnering with William Jackson, the two operated the mill for almost 10 years. By the 1880s, Sheldon “Pudy” Pharis had purchased property in the upper Little Butano basin. Known as the “shingle king,” Pharis built one of the first shingle mills in the Santa Cruz Mountains in 1863, and apparently operated as many as seven mills. Pharis purchased the Taylor mill, along with many others in the area. In 1885, however, Pharis committed suicide, and the mill ceased operation.

(14).JPG) Peninsula Farms

Peninsula Farms

Several parcels of land north of Gazos Creek, including Little Butano Flats were developed into a farming cooperative known as Peninsula Farms beginning in 1923. The property was subdivided in into 41 parcels, many of which were further subdivided in later years. A manager of the cooperative built what is now the lower park residence, as well as the flume on Little Butano Creek.

New Ownership

In the 1920s, the Goat Hill property was purchased by Peter Olmo. Olmo operated a dog kennel, as well as a small turkey farm on the property. At roughly the same period, Joe Bacciocco purchased the Jackson property, along with the house built by the Peninsula Farms. Bacciocco, a wealthy San Franciscan meat wholesaler, did not live at the house, but instead used it as a weekend retreat. Bacciocco hosted parties that became infamous during the period of Prohibition. He hired local resident Hans Carlson to serve as caretaker for the property from 1936 to 1952. Land speculators initiated the purchase of much of the Bacciocco property, surveying forty homesites. Many of these homesites were in the location of what would become the present campground. The drastic decline of the stock market in 1929 sealed the fate of the land speculators, and no development occurred in the area. Bacciocco retained ownership of the land.

As described above, this region soon became a rich lumber resource. Several lumber companies acquired vast tracts of land in what is now Butano SP. A large area in the watershed of Pescadero Creek was known as “The Butano,” and was owned by the Western Shore Lumber Company and Mr. T.J. Hopkins. This area generally was centered on Butano Creek. The Butano Development Company owned several private holdings in this area “for subdivision as camp sites”. Land encompassing the watershed of the Little Butano Creek was owned by those individuals described above, as well as extensive holdings by the Pacific Lumber Company.

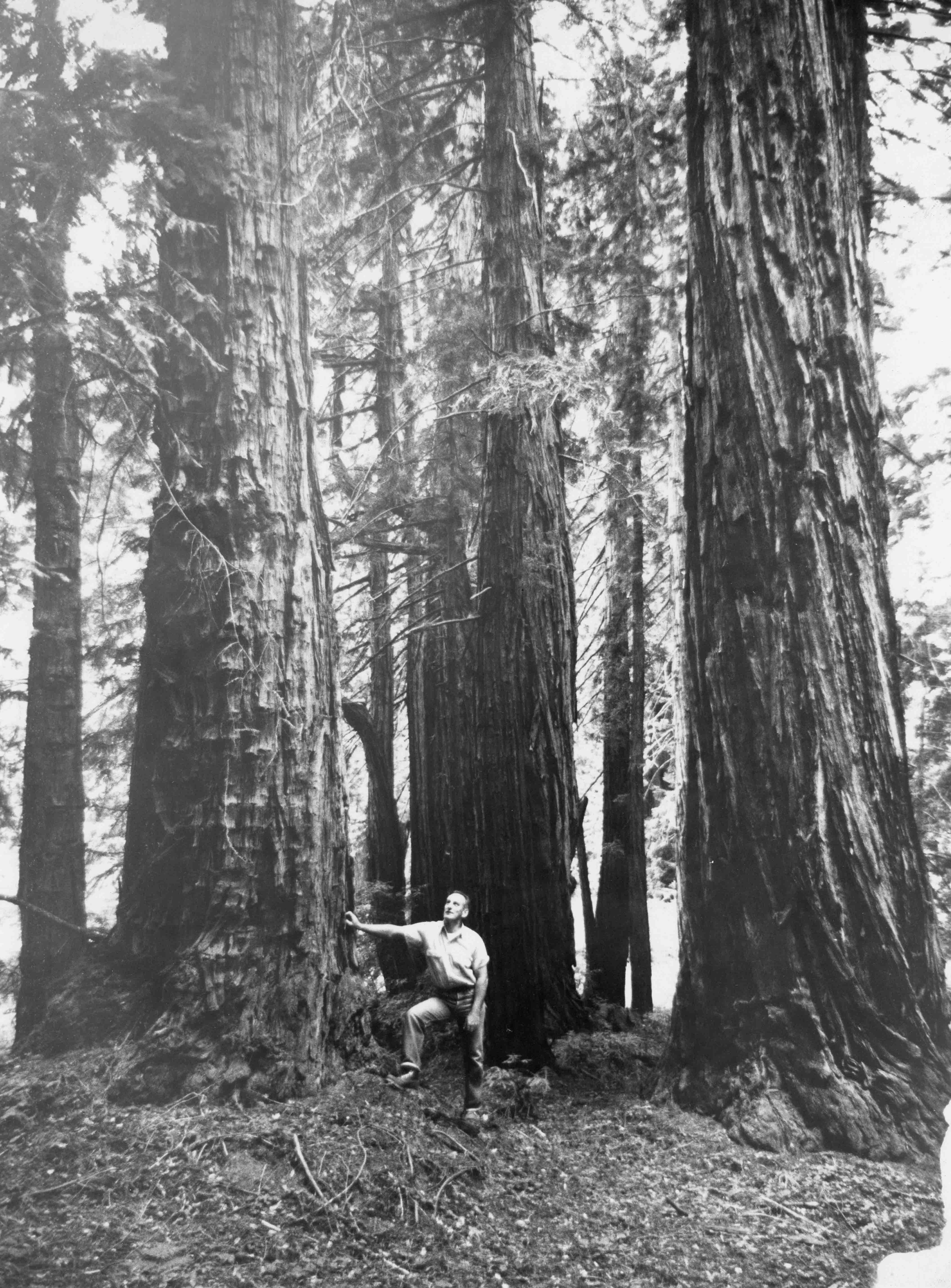

Early Preservation

Efforts Conservation groups had been lobbying to preserve California’s coastal redwoods beginning in the 1880s. This movement had its earliest and brightest victory in the creation of Big Basin Redwoods State Park in 1902. By 1921, the preservation group Sempervirens Club set their sights upon land along Butano Creek, which contained some of the best remaining stands of old growth redwoods in the state. In 1928, a statewide park survey called for the addition of 12,000 acres to Big Basin Redwoods State Park (encompassing Butano Creek). Though timber prices declined over the next few years (and thereby the value of the land), funds were not available for this purchase. As they had in the past, timber prices rose again, and logging activity was renewed in the early 1930s. In 1932, the Save-the-Redwoods League commissioned a study for the potential for a park in the Little Butano Creek area though no land purchases were made. By World War II, the Pacific Lumber Company had purchased a great deal of the property in the area surrounding the valley of Little Butano Creek. Meanwhile, in 1941, San Mateo County planned to purchase 160 acres in what was referred to as the Butano tract (along Butano Creek). The county planned to develop the area for recreation with the assistance of the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). This plan did not come to fruition, likely as a result of the war.

Efforts Conservation groups had been lobbying to preserve California’s coastal redwoods beginning in the 1880s. This movement had its earliest and brightest victory in the creation of Big Basin Redwoods State Park in 1902. By 1921, the preservation group Sempervirens Club set their sights upon land along Butano Creek, which contained some of the best remaining stands of old growth redwoods in the state. In 1928, a statewide park survey called for the addition of 12,000 acres to Big Basin Redwoods State Park (encompassing Butano Creek). Though timber prices declined over the next few years (and thereby the value of the land), funds were not available for this purchase. As they had in the past, timber prices rose again, and logging activity was renewed in the early 1930s. In 1932, the Save-the-Redwoods League commissioned a study for the potential for a park in the Little Butano Creek area though no land purchases were made. By World War II, the Pacific Lumber Company had purchased a great deal of the property in the area surrounding the valley of Little Butano Creek. Meanwhile, in 1941, San Mateo County planned to purchase 160 acres in what was referred to as the Butano tract (along Butano Creek). The county planned to develop the area for recreation with the assistance of the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). This plan did not come to fruition, likely as a result of the war.

Post World War II

Landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., under contract with the state, surveyed the Little Butano area in 1946, recommending that a park not be considered for this region. Olmsted instead urged the acquisition of land in the Butano area. This area was favored by most conservationists, while Little Butano was not. Conservationists had, by this time, placed emphasis not only on saving the old growth redwoods, but also providing easy access to them by the large metropolitan areas of the San Francisco Bay area. Conservation efforts, however, were helped by the fact that Butano remained a rugged and relatively inaccessible area, making development difficult. The decline of lumber prices following the end of World War II also assisted in the conservation efforts. Efforts were again made to purchase the Butano beginning in the late 1940s. Many private groups (perhaps foremost among them the Loma Prieta Chapter of the Sierra Club) sought the establishment of a state park in the area. The State Park Commission was apparently convinced, and planned to acquire 4,500 acres encompassing Butano and Little Butano valleys. The commission set aside funds to purchase sections of the land on a matching basis. San Mateo County agreed to donate their tract of land in the area, known as the San Mateo County Memorial Park. In 1954, the state appraised 1,040 acres in the Butano area at $800,000. The owner (presumably the Pacific Lumber Company), however, would not sell for less than $1,600,000. The State Park Commission prepared to initiate condemnation proceedings. Lacking the support of local counties (San Mateo, San Francisco, and Santa Clara), the Commission began looking at alternate areas, including the Little Butano area.

The Butano Forest Associates was formed to assist the state in acquiring and preserving 5,000 acres of the Butano and Little Butano watersheds. In 1951, the organization agreed to donate $5,000 in exchange for having a 40-acre redwood grove named for their organization. Apparently, the Division of Beaches and Parks agreed, and accepted the money. The first acquisition was made in 1956, consisting of 320 acres of government land. Soon thereafter it was designated “The Butano.” Olmo’s property, including their residence, was deeded to the state on March 31, 1958. In 1959, the state had acquired a total of 1,900 acres. Much of this land had already been logged extensively, and those trees remaining were primarily second growth. The park was not open to the public until many years later, when facilities were completed.

A request for $336,489 was made in the 1962/1963 budget for the first phase in the development of a 90-unit campsite in the new park. The first campground included 40 units with a graded dirt road, water system, and a single comfort station. In 1961, Benjamin Ries, Park Supervisor of the newly formed Butano SP, was killed in an accident at the park. Soon thereafter, the campground was named in his honor. Plans were made for many more campgrounds, along with improved roads, trails, comfort stations, combination buildings, and electricity. The road through the park to the campground was completed in 1964 (with a bridge over the creek constructed that year). Overhead power lines were finally installed in 1967. By 1980, the park contained 2,186 acres.