Education on the Frontier: The Mason Street Schoolhouse

By Nathan Fogerson, San Diego State University Intern, Spring 2021

In the nineteenth century, access to quality public education on the frontier of America was rare. San Diego was no exception, even prior to California being admitted to the United States of America. While still under Mexican control, many children in San Diego had no access to free public education. If a parent desired to get their child a decent education, they had to be prepared to pay for private tutors who would educate their children. Further attempts to open more schools in San Diego were made while the area remained under Mexican control, but ultimately no substantial progress was made.

Access to education became a priority in San Diego after the city formed in 1850. November 1850 was an especially contentious month in Old Town, as discussions on where and how to have a school swirled among local residents. One of the first ideas proposed included renting a room in a local house to serve as a classroom. This idea met some initial resistance by members of the community who felt that such a room would not be adequate to serve as a school. Despite the opposition raised by some members of the community, the idea was approved by the city council. However, the teacher at the time did not feel the room was adequate, and told city officials that she was unwilling to teach in the room being rented.

As a result, the City Marshal was tasked with trying to find a suitable room to serve as a school. So, with his own personal interest in mind, he offered to rent out rooms he owned for a price of sixty dollars a month. The offer was accepted by the city council, but the school never materialized. The city of San Diego made some additional attempts to establish a working public school in 1850, but despite the best intentions of the city council, nothing substantial was established in the first decade of the city’s history. It would not be until the 1860s that an adequate school building was built.

In 1865, the situation regarding public education in San Diego changed dramatically. Fifteen years after San Diego was officially incorporated as a city, its first public school was finally built. The original building was rather modest in size. Only 24 by 30 feet, or 720 square feet, with a 10-foot ceiling, it did not have a library. For comparison, contemporary classrooms can easily be more than 1,000 square feet to accommodate students. However, there were other challenges with this plan. The district that the school served was around 14,000 square miles and included parts of modern-day San Diego County, Imperial County, and Riverside County—obviously young students could not travel large distances each day to get to school. Finding a teacher was another problem, but later in the year, a woman named Mary Chase Walker accepted the position.

Mary Chase Walker was born in Massachusetts and had a long history of teaching. In fact, she first started teaching at only 14 years old, and earned a salary of four dollars. Walker later attended the State Normal School in Framingham, Massachusetts, where she graduated in 1861. Shortly after her graduation, she returned to teaching, but this time earned a salary of four hundred dollars a year. It is important to note that when the American Civil War broke out in the early 1860s, many women, including Walker, became teachers in place of men who were fighting in the war. Finally, in 1865, Mary decided to come out west, taking a steamer from New York and ending up in San Francisco. After finding no teaching jobs in San Francisco, she went down to San Diego after hearing the town was looking for a teacher. She officially took the job as a teacher at the Mason Street Schoolhouse. Here in San Diego, she received a salary of sixty-five dollars a month for her services.

Despite the promise she showed, Mary Chase Walker only served eleven months as the teacher of the schoolhouse. There was a confluence of events that ended her teaching career. First, she invited an African American woman out to lunch with her. Because racist social norms discouraged relationships between white and Black people, Walker faced scrutiny despite receiving some support from the community. The other major factor was that she married the school superintendent Ephrain Morse, and once married, women did not traditionally continue their careers. Walker did not fade away completely, however, as it is reported that later in life, she was involved with supporting the suffrage movement and worked to help those in need.

|

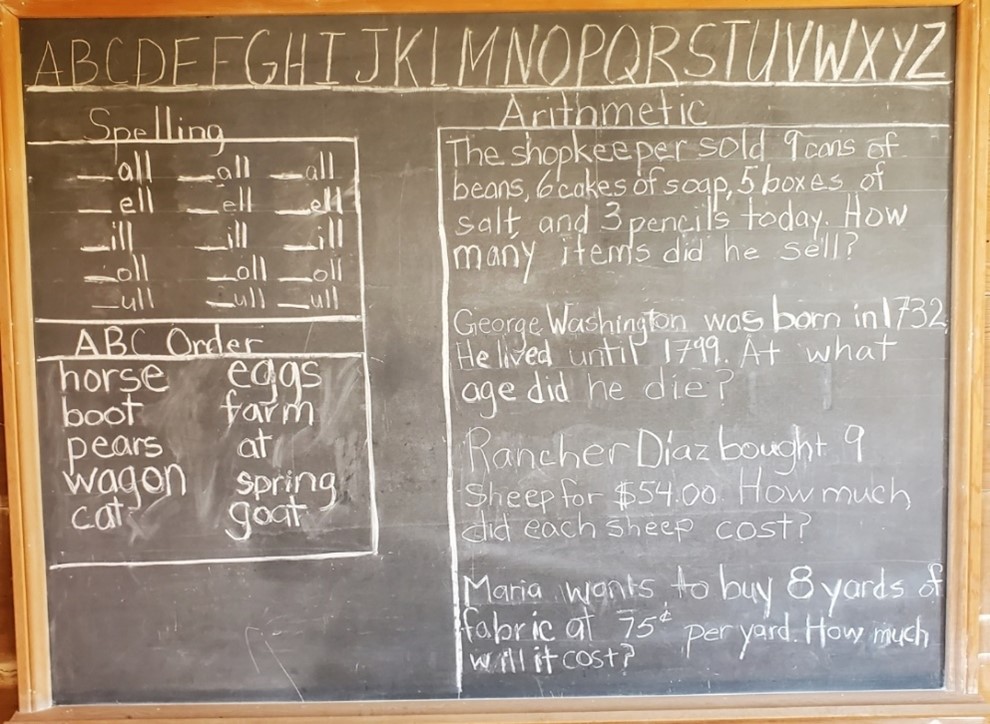

During Mary Chase Walker’s short tenure, education was very different than what students experience today. With the building only having one room, there was no separation of students based on age or education level. The school year also looked different. In 1865, the school year was July through May. Students of all ages received the same education at the same time. That standardized education included reading, writing, and arithmetic. The modest school was small both physically and in its attendance. In 1866, for example, the average number of students enrolled in the school was 42, but those students were not always present. In fact, having absent students was a common problem at the time. On any given day, approximately a third of all students would be absent from school. Absence from school could have occurred for a variety of reasons. Most commonly, students would be absent due to local events going on in the town such as fiestas and rodeos. Beyond local events, assisting the family at home often took priority over education for the majority of students.

|

The importance of the Mason Street Schoolhouse cannot be overstated, as it was the first public school in San Diego. Merely by being open, the schoolhouse provided an opportunity for education that had never been afforded to people in San Diego before. Getting an education could serve as a life changing event for someone as they could use it to get better jobs and provide a more comfortable life for themselves and their families. The Mason Street Schoolhouse served San Diego as a hub for education until 1872.

After construction of another school began in 1872, the Mason Street Schoolhouse was closed. The building was then taken apart and rebuilt at another location where it served different purposes, such as a family home, and later, a tamale restaurant that operated out of the building until 1952. Eventually, the building was acquired by the San Diego County Historical Days Association (SDCHDA) in 1952. That organization was able to stop the building from deteriorating further and helped restore it. The building was transferred to where it stands today in Old Town San Diego State Historic Park and renovated to look like a typical one room schoolhouse of the time. In 2013, SDCHDA transferred ownership of the building to the State of California, and it has since become a California State Landmark. The original schoolhouse still serves its purpose as a place of education well into the twenty-first century, as it helps provide students from all around San Diego County an idea of what school was like in the nineteenth century.

Additional Resources

In-depth article about education in San Diego:

https://sandiegohistory.org/archives/books/smythe/part6-2/

Biography of Mary Chase Walker:

https://sandiegohistory.org/archives/biographysubject/mcwalker/

San Diego City Council minutes and ordinances form 1850 till 1874:

https://www.sandiego.gov/sites/default/files/1850a.pdf