Wakamatsu Tea and Silk Colony

by Christopher Corey, Associate State Archaeologist

Three miles from the site of Sutter’s Mill, where gold was discovered in 1849, is a small marble headstone on a knoll that reads: “In Memory of Okei, Died 1871, Age 19 Years, A Japanese Girl” in English and Japanese. The story of how this monument came about near the town of Coloma is the story of a bold adventure of a group of Japanese settlers who are reputed to be the first Japanese immigrants to arrive in the New World.

In the spring of 1869 a group of twenty two Japanese settlers arrived in San Francisco aboard the steamship “China”. Fleeing civil war in Japan, they had come from Aizu Wakamatsu City, on the island of Honshu, to the United States in hopes of establishing permanent agricultural colony in California. The settlers made their way by boat up the Sacramento River, and then overland to El Dorado County, where they established the Wakamatsu Tea and Silk Colony on 640 acres.

A second group of colonists arrived from Aizu in the fall of 1869. The colonists arrived with thousands of mulberry trees for silk worms to feed on, as well as tea plants, bamboo roots, and other Japanese agricultural products. The colony prospered, and in 1870 they entered their tea plants and plant oils in the San Francisco Horticultural Fair. The Colony began to fall on hard times in the early 1870s due to an extended drought and a lack of anticipated financial assistance from Japan. By June of 1871, the colony had to be sold because of the extended drought and financial difficulties. Many of the colonists dispersed to San Francisco; some went back to Japan, and a few stayed behind with the Veerkamp family, who were local landowners. One of the colonists who stayed to live with the Veerkamps was a young girl named Okei. She arrived at the colony in 1870, and in 1871 she came down with a high fever and subsequently died. The cause of her death is thought to be malaria. She was buried on a small knoll where she had enjoyed evening walks to take in views of the setting sun.

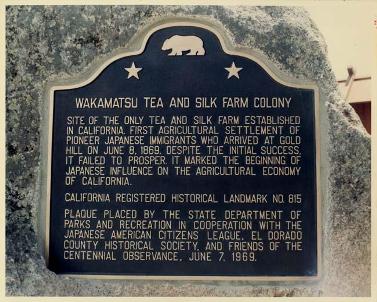

Okei and the Wakamatsu Colony faded from memory until the 1950s, when local historians and Japanese Americans began to research the colony and conducted interviews with Henry Veerkamp, the son of the Veerkamps who took in the remaining colonists when the agricultural venture fell on hard times. Henry revealed the location of the forgotten colony and Okei’s grave. In 1969, the State of California officially recognized the centennial year of Japanese immigration to the United States with a historical plaque. Then-governor Ronald Reagan and the Japanese Consul General Seiichi Shima designated the Wakamatsu Tea and Silk Farm Colony as California Registered Historical Landmark Number 815 on June 7, 1969. The monument states, in part; “…The beginning of Japanese influences on the agricultural economy of California.”

Okei and the Wakamatsu Colony faded from memory until the 1950s, when local historians and Japanese Americans began to research the colony and conducted interviews with Henry Veerkamp, the son of the Veerkamps who took in the remaining colonists when the agricultural venture fell on hard times. Henry revealed the location of the forgotten colony and Okei’s grave. In 1969, the State of California officially recognized the centennial year of Japanese immigration to the United States with a historical plaque. Then-governor Ronald Reagan and the Japanese Consul General Seiichi Shima designated the Wakamatsu Tea and Silk Farm Colony as California Registered Historical Landmark Number 815 on June 7, 1969. The monument states, in part; “…The beginning of Japanese influences on the agricultural economy of California.”

In 2007, the California Legislature had Governor Schwarzenegger proclaim May 20th as Wakamatsu Tea and Silk Colony Day to encourage recognition of the Colony and to educate the public on the Japanese American Roots of California agriculture. View Senate Concurrent Resolution

This pioneering settlement is the first Japanese community to establish themselves in California. All that remains of these settlers is Okei’s gravesite and the ranch house where the colonists once resided. They are currently on private property. The Gold Hill Ranch is now 303 acres of abandoned pasture lands. The American River Conservancy and local Japanese Americans are working toward purchasing the ranch property to establish a preserve in honor of the lasting legacy of this significant historical site.