Monarch Butterflies

The Monarch Grove at Pismo State Beach is publicly owned assuring its protection into the foreseeable future. Sites on privately owned land may not be as safe since development is reducing preserved space at an alarming rate. Although the Monarch Butterfly is not now an endangered species, biologists are beginning to worry about the survival of this amazing insect. Pismo State Beach is one of the largest monarch groves in the United States. The butterflies that come here are part of an ongoing study. A tagging program is helping scientists discover more about life patterns of the Monarchs. Monarch clusters, though in fewer numbers, are found throughout coastal San Luis Obispo County.

What is so special about the Monarch butterfly?

Along with the astonishing numbers found at over wintering sites along the California coast, even more astonishing is the story of how they got here. Two populations of Monarch butterflies call the United States home. The group living east of the Rocky Mountains migrates south to spend the winter in Mexico. Those living west of the Rockies migrate to the coast of central and southern California. Migration is not an uncommon phenomenon. So, what is so unusual about the Monarch butterfly migration? Let’s follow them. The western Monarchs’ summer range extends from the Rockies to the Pacific Ocean and north as far as southern Canada. In October, as colder weather approaches, the butterflies instinctively know they must fly south to escape the freezing temperatures. Some have to fly over 1,000 miles. The journey is hazardous and many never make it. By November, most are sheltering in trees stretching from the San Francisco Bay Area south to San Diego. Pismo State Beach hosts one of the largest over wintering congregations, varying in numbers from 20,000 to 200,000. The winter monarchs live about six to eight months. On sunny winter days they will fly away from the sheltering trees, searching for nourishment in flower nectar and water to drink. In late February, as the weather turns warm, the great migration north begins.

Along with the astonishing numbers found at over wintering sites along the California coast, even more astonishing is the story of how they got here. Two populations of Monarch butterflies call the United States home. The group living east of the Rocky Mountains migrates south to spend the winter in Mexico. Those living west of the Rockies migrate to the coast of central and southern California. Migration is not an uncommon phenomenon. So, what is so unusual about the Monarch butterfly migration? Let’s follow them. The western Monarchs’ summer range extends from the Rockies to the Pacific Ocean and north as far as southern Canada. In October, as colder weather approaches, the butterflies instinctively know they must fly south to escape the freezing temperatures. Some have to fly over 1,000 miles. The journey is hazardous and many never make it. By November, most are sheltering in trees stretching from the San Francisco Bay Area south to San Diego. Pismo State Beach hosts one of the largest over wintering congregations, varying in numbers from 20,000 to 200,000. The winter monarchs live about six to eight months. On sunny winter days they will fly away from the sheltering trees, searching for nourishment in flower nectar and water to drink. In late February, as the weather turns warm, the great migration north begins.

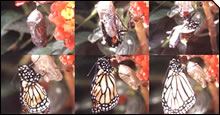

After a flurry of mating, the female Monarchs fly north seeking milkweed plants where they must lay their eggs. Their job done, the winter Monarchs soon die. It would seem as though the migration had come to a halt before it even got under way. This though, is  where it gets interesting. The eggs hatch after a few days and the tiny larvae voraciously begin eating milkweed leaves day and night. Milkweed is the only food the larva can eat but it eats enough to increase its weight 2,700 times in just two weeks. This is equivalent to a human baby growing to the size of a gray whale in just two weeks! Once it’s eaten its fill, the fullgrown caterpillar attaches itself to a solid object, sheds its skin, and forms a hard,

where it gets interesting. The eggs hatch after a few days and the tiny larvae voraciously begin eating milkweed leaves day and night. Milkweed is the only food the larva can eat but it eats enough to increase its weight 2,700 times in just two weeks. This is equivalent to a human baby growing to the size of a gray whale in just two weeks! Once it’s eaten its fill, the fullgrown caterpillar attaches itself to a solid object, sheds its skin, and forms a hard,  green and gold colored outer skin called a chrysalis. For the next two weeks inside the chrysalis, the fat, striped caterpillar rearranges its body’s molecules and then emerges as a beautiful orange and black Monarch butterfly. The new summer Monarchs continue to fly farther north, mating, laying their eggs on milkweed, then dying. The summer monarchs only live about 6–8 weeks but each new generation flies farther and farther north, following the growing milkweed. This cycle repeats itself 4–5 times throughout the summer. It is unknown how the successive generations of butterflies inherit the information needed to return to the over wintering sites but with the shortening days of October, the new winter generation of Monarchs does not mate and die but instead migrates south. How do they know where to go? Experience the mystery of these butterflies, enjoy their beauty, and learn more about their fascinating behavior at Pismo State Beach.

green and gold colored outer skin called a chrysalis. For the next two weeks inside the chrysalis, the fat, striped caterpillar rearranges its body’s molecules and then emerges as a beautiful orange and black Monarch butterfly. The new summer Monarchs continue to fly farther north, mating, laying their eggs on milkweed, then dying. The summer monarchs only live about 6–8 weeks but each new generation flies farther and farther north, following the growing milkweed. This cycle repeats itself 4–5 times throughout the summer. It is unknown how the successive generations of butterflies inherit the information needed to return to the over wintering sites but with the shortening days of October, the new winter generation of Monarchs does not mate and die but instead migrates south. How do they know where to go? Experience the mystery of these butterflies, enjoy their beauty, and learn more about their fascinating behavior at Pismo State Beach.